The five most beautiful churches in Vienna: part 3 – the Wotruba Church

The Wotruba Church, also called the Church of the Most Holy Trinity

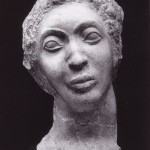

The church is a clear statement of modern sculpture… yes, you read correctly: sculpture! Its architect was namely the Austrian sculptor Fritz Wotruba.

…unfortunately still a vastly underrated Austrian sculptor.

About Fritz Wotruba

Wotruba was born in Vienna in 1908, the son of a tailor’s assistant. He originally learned the stamp engraver’s trade. Starting in 1926, he attended public night school and nude drawing

classes of the Austrian Museum of Art and Industry’s (today’s Academy of Applied Arts) School of Applied Arts. He remained a student of Anton Hanaks and Eugen Steinhof up until the completion of his training in 1928. In 1929, after disciplinary proceedings due to interfering with a dispute between Prof. Steinhof and his future wife Marian Fleck, he was expelled from the Academy, albeit with a positive school-leaving certificate.

During the course of his studies with Prof. Steinhof, he met the daughter of a Jewish merchant, Marian Fleck, whom he married in 1929.

In the 1930s he established friendships with many—nowadays—famous artists of his time, among them Elias Canetti, Hermann Broch, Herbert Boeckl and the composer Alban Berg. He also taught drawing to Anna Mahler, with whom he enjoyed lively exchanges of ideas. He took part in the Biennale in Venedig already in 1932 and 1936.

When the National Socialists assumed power, he emigrated to Switzerland for political and economic reasons.

It was not until 1945 that he returned to Vienna, following an arrangement on the part of Herbert Boeckl for him to chair the sculpture master class at the Academy of Fine Arts, which he held up until his death in 1975. Amongst his most famous students were the sculptors Avramidis and Alfred Hrdlicka (whose “Memorial Against War and Fascism” can nowadays be seen at

Albertina Square in Vienna). As a representative of Austria, he took part in documenta II (1959), documenta III (1964) and documenta VI (1977) in Kassel.

Despite the many efforts on the part of the Fritz Wotruba Private Foundation, the former director and Egyptologist of the Vienna Museum of Art History, Dr. Wilfried Seipel, and the collaboration of Dir. Agnes Husslein-Arco (the current director of the Belvedere) and the jointly produced special exhibition in the Lower Belvedere in 2007, Fritz Wotruba’s complete works are unfortunately still not known to a broad public.

Perspectives – 21er Haus

After a single location for Wotruba’s works had long been considered, with the 21er-Haus—newly reopened in 2012 from the former 20er Haus—a worthy presentation area for one of the most important 20th-century Austrian artists was at long last found.

The works

In his works, Wotruba oriented himself heavily towards classical models of antiquity, as well as—and above all—to Renaissance architecture. This development can be clearly seen from the formal language of his early works (see photos). He gradually succeeded in developing his own flow.

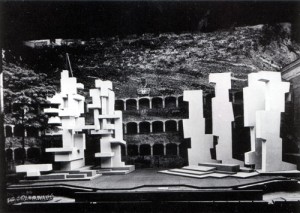

In view of his late works, the work for the stage plays a not inconsiderable role in his oeuvre—precisely in view of the construction of the Church of the Most Holy Trinity.

Amongst his other stage work, Fritz Wotruba designed the set for King Oedipus in the Burgtheater (Vienna, 1960) and in 1965, also for King Oedipus, likewise created the set for the Salzburg Festival. This merits special attention in this context, since the artist himself had emphasized that, with the commission for the church in 1971, he “would finally get away from ‘artificial’ theater architecture and arrive at genuine architecture.”

Wotruba: “If this construction succeeds, it will be one of great dynamics and drama. The apparent chaos that arises from the arrangement of asymmetric blocks should ultimately result in a harmonic unity.” (The italicized text is taken from the foundation’s site; the reference can be found here.) It was this development and emancipation from his models that finally led him to formal abstraction and thereby to applied rhetoric, as we find in the Church of the Most Holy Trinity.

The church – climax and culmination

The church was already commissioned in 1971 and could only be built, after considerable struggle, between 1974 and 1976, under chief architect Fritz Mayr. It was not dedicated until a year after Wotruba’s death. Today, it is an excursion destination that enjoys great popularity amongst the populace.

152 concrete blocks form an apparently chaotic and random mountain of differently sized ashlars. Unsurprisingly for Wotruba’s work and thought, the façade has no display side or dome superstructure, for instance. Rather, the whole results from the interplay of the individual construction elements. Stylistically, it is classified as brutalism. The emphasis lies on the primitiveness of the components used. Like a tectonic impact, the slabs, ashlars and cubes seem to shift and rearrange themselves with every step. In such cases, one speaks of polyvalence (ambiguity). In the spirit of the architect, there is no clearly defined inside or outside—and precisely therein lies the great strength and the true originality of the church. Viewers as well as

visitors are thereby invited to take part in a permanent dialog. Exterior becomes interior, only to become the exterior once again. This statement is underscored by the manifold omissions amongst the individual components. Like countless streams, fountains of light pour into the interior, thereby making a dynamic and ever-changing oscillation of light possible. By uniting apparent contradictions, such as horizontal and vertical, interior and exterior, above and below, light and dark, fragment and finality, Fritz Wotruba demonstrates his cosmopolitan worldview that was constantly at pains to unite the incompatible, to reconcile the irreconcilable.

The church thus constitutes a monumental conclusion to and is simultaneously the climax of his work, output and thought. In the realization of this unique idea as a church, one probably has to grasp a reconciliation of the terrors and consequences of the Shoha of the 2nd World War.

The copyright of the title photo can be found here.

The copyright of all other photos can be found by clicking on them.

Next article: the most beautiful churches in Vienna: part 4 – the Otto Wagner Church